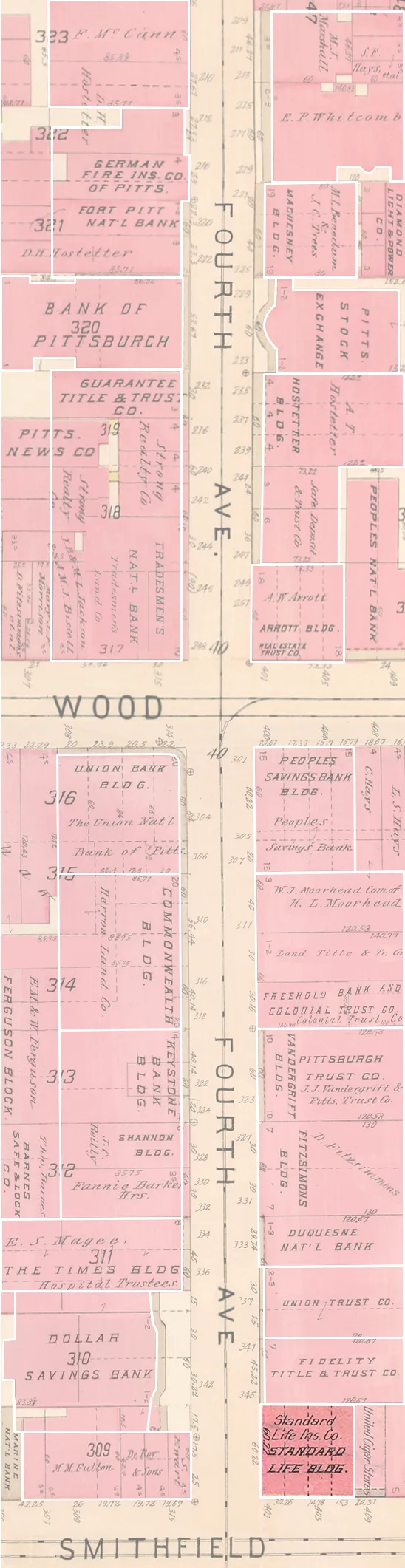

Standard Life Building

A flurry of skyscraper construction including this building, erected in 1900, dramatically changed downtown Pittsburgh at the turn of the last century. It was designed by Andrew Carnegie’s favorite architects, Alden & Harlow, who built several office towers in the city, including a similar one at the opposite end of this block.

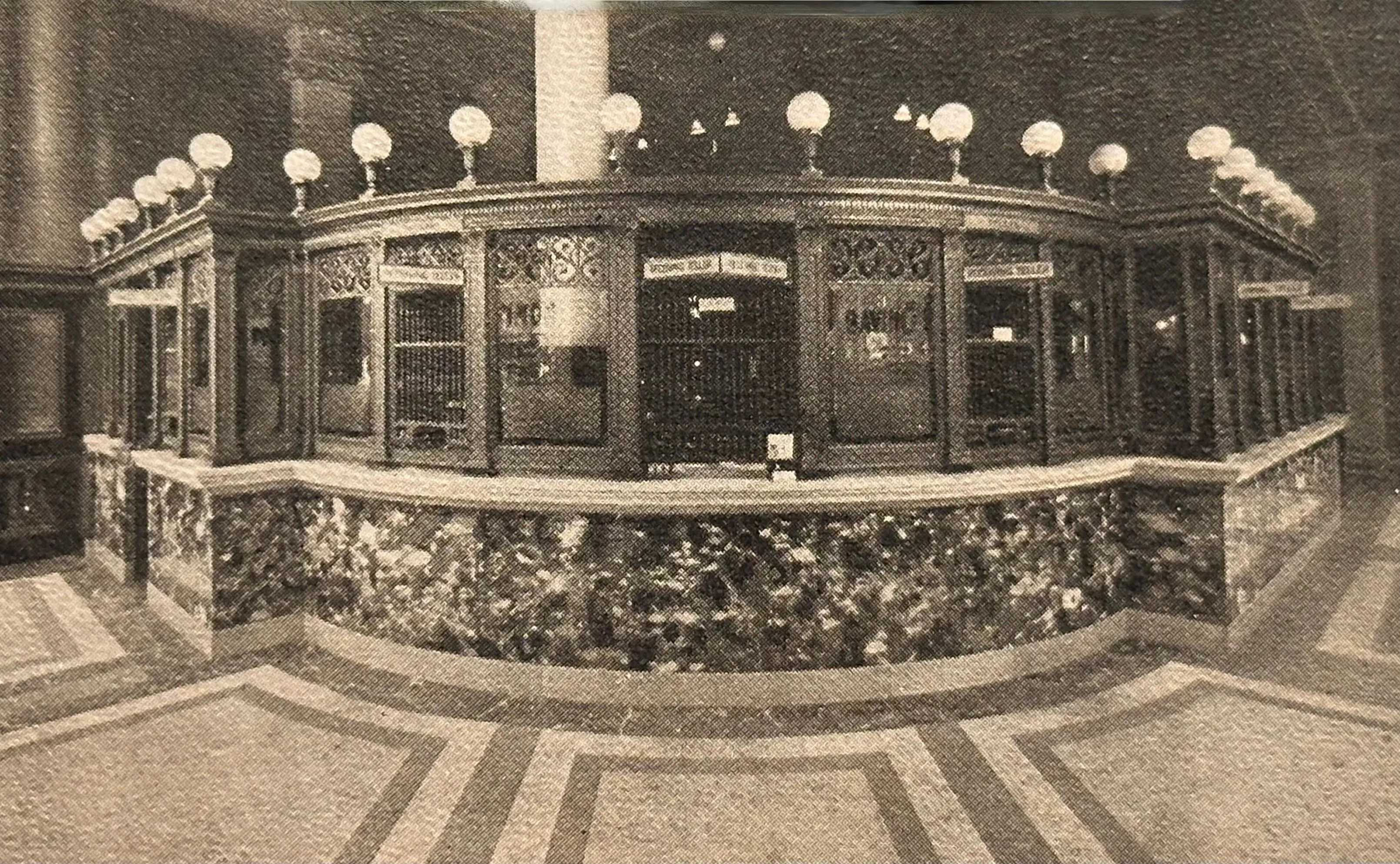

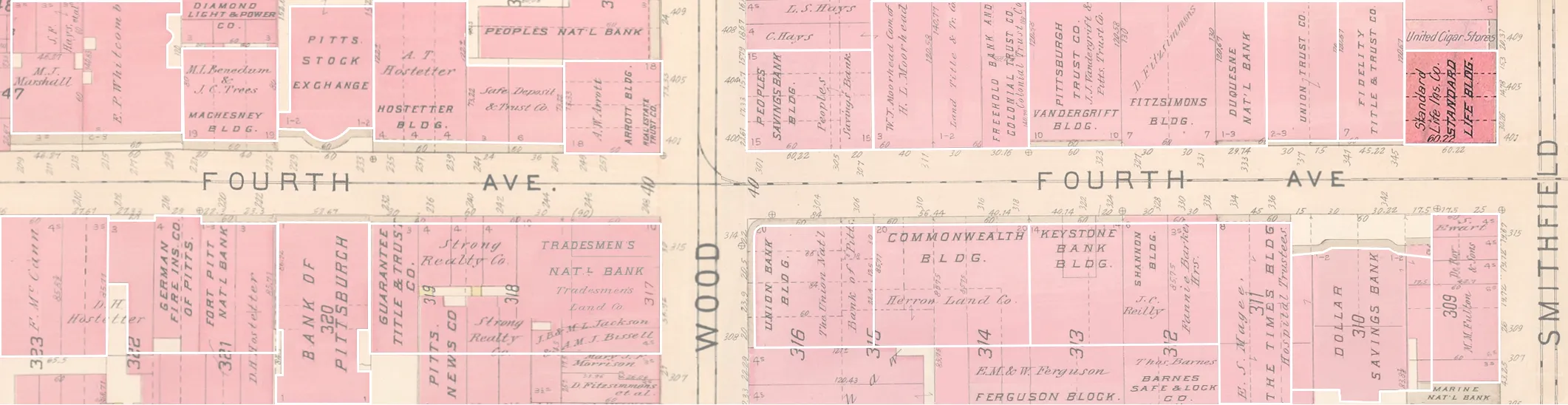

The Standard Life Building was originally the headquarters of the Pittsburgh Bank for Savings, one of the financial institutions crowding this stretch of Fourth Avenue that gave it the nickname “Wall Street of Pittsburgh.” The Pittsburgh Stock Exchange was on the second floor, but only for two years, until the traders chose new quarters down the street.

The bank failed in 1915, and the Standard Life insurance company bought the property and moved in shortly thereafter. That company’s president, John Hill, was a vocal proponent of the temperance movement and introduced a life insurance policy for non-drinkers. Today, like many of the antique skyscrapers of Fourth Avenue, the building has been converted into residential use.

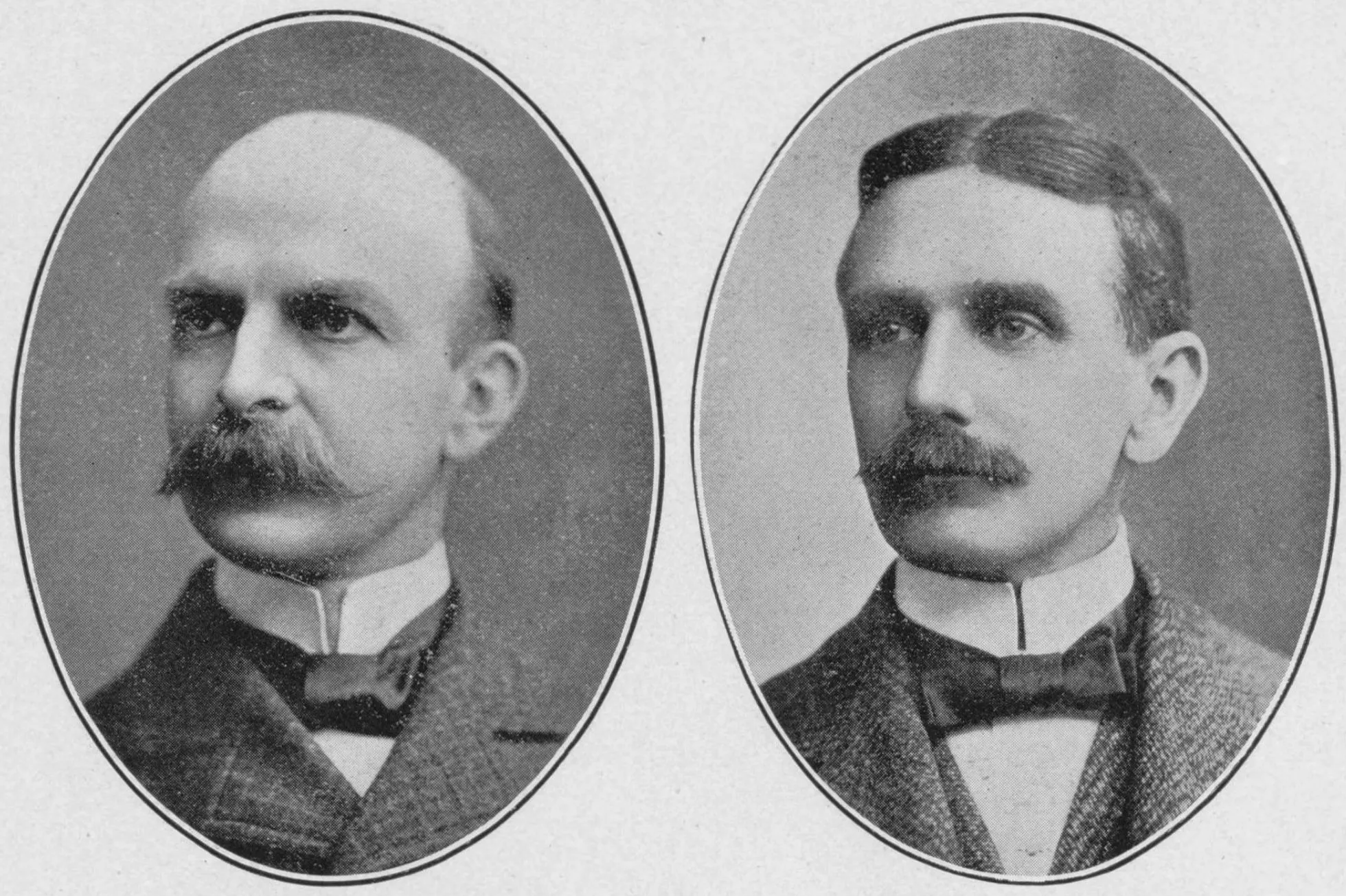

Alden & Harlow

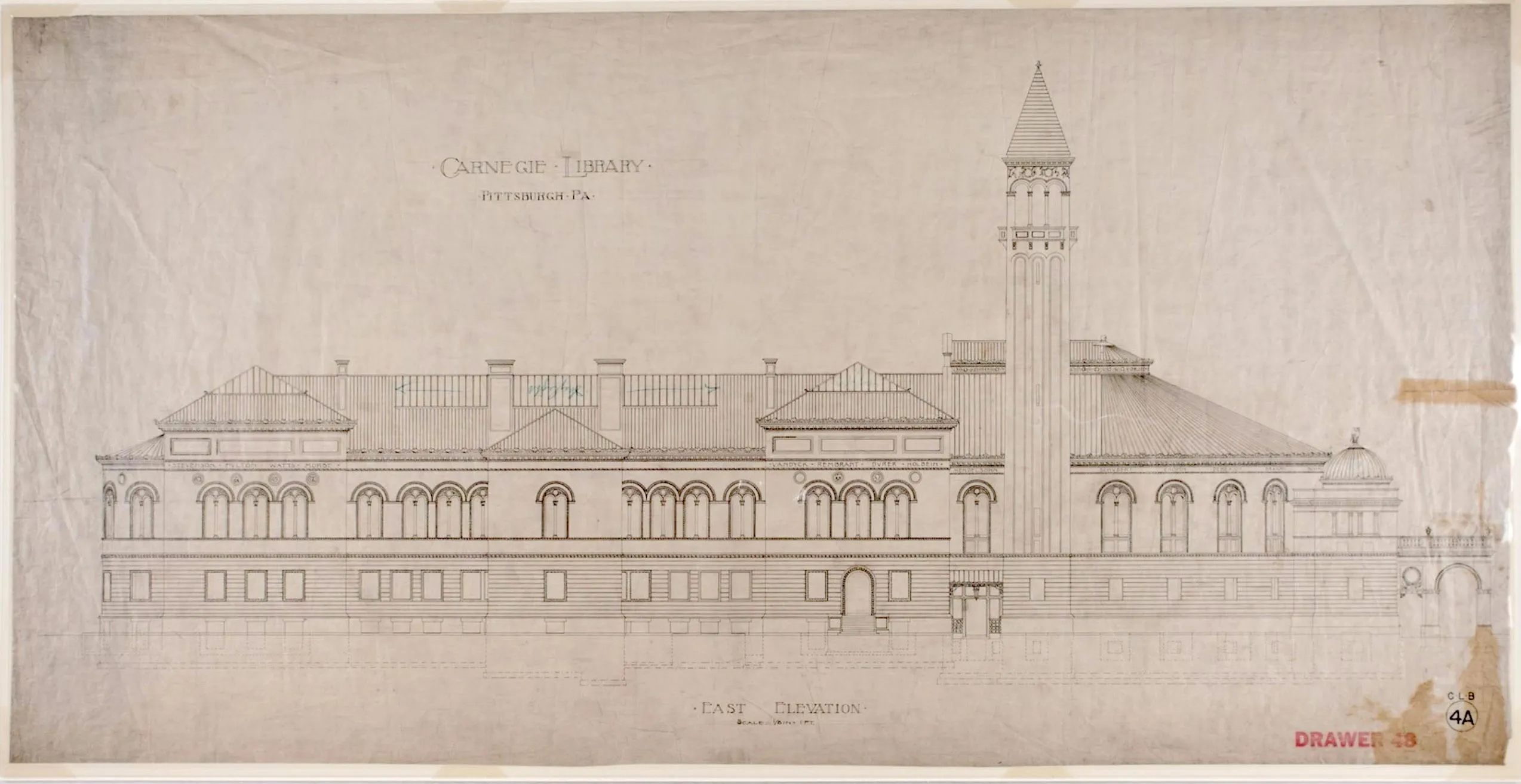

Originally a Boston practice, these architects relocated to Pittsburgh as its booming local economy spurred lucrative commissions for skyscrapers and other big projects, plus mansions for the nouveau riche. Frank Alden came here first to supervise construction of Henry Richardson’s monumental Allegheny County Courthouse. He was later joined by Alfred Harlow after their firm won a contract to design the Carnegie Institute, a huge edifice in Oakland combining a library, music hall, and museum.

The partners went on to design several Carnegie Library branches, as well as the Duquesne Club and numerous early Pittsburgh skyscrapers. Their Carnegie Building on Fifth Avenue, demolished decades ago, was the tallest skyscraper in the city when it opened in 1895.

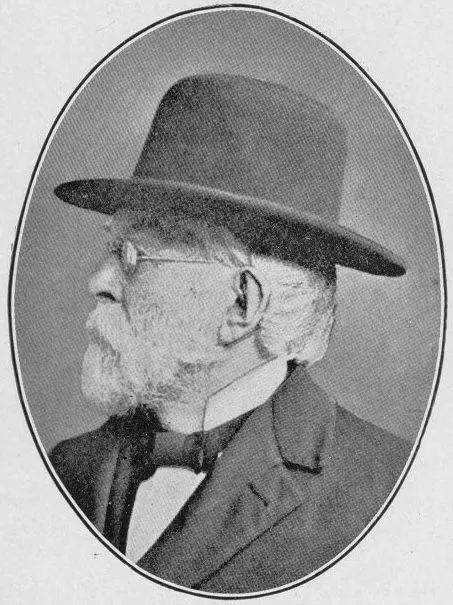

George Berry

The longtime former president of the Pittsburgh Bank for Savings was still a trustee when this skyscraper went up. As a young man he was a sales agent for DuPont gunpowder and built a powder magazine in the Hill District. Later on, he manufactured chemicals and window glass.

Berry was named to a three-person commission appointed by city council to choose a site for a reservoir in 1870; they selected Highland Park. His successor as bank president, James Kuhn, also had a background in constructing waterworks. When the first public drinking fountain opened in Pittsburgh in 1903, it was sponsored by the bank and stood on the sidewalk outside the main entrance.